Good Coding Practices

Tips:

.Rproj可以用起来- 需要经常重启。

重启会删除一些中间存储变量,再次运行,确保代码正确,以及借此机会重新整理代码。

Project Structure

项目整体结构 project file structure

-

Avoid writing excessively long scripts; do one thing in one script; 一个文档做一件事

If it is difficult to understand your code without comments, this can indicate that your code is too complex and might benefit from being broken down, or “refactored”, into smaller units.- Start with file description about what this file does, what output it generates; preferably add edit time;

- Last edit:

yyyy-mm-dd(ISO 8601); to show when you change the script last time;

- Last edit:

- Date naming convention:

yyyy-mm-dd; add date to output files to indicate historical versions;

- Start with file description about what this file does, what output it generates; preferably add edit time;

- Script naming conventions:

1-1-1_function-of-script;-

If files need to be run in sequence, prefix them with numbers:

The first digit denote main procedures; the second denotes sub-procedures, the third denotes various versions;

-

function-of-scriptdescribes what the script does;

Should follow “Context + verb + noun”. Scripts that belong to the same context should start with the same prefix, i.e., context. -

Do not name image files as “Figure1.png”, “Figure2.png”, “Figure3.png”, etc., because their positions may change later. → Name them based on their content instead.

画图文件不要用图1,2,3来命名,因为后期可能调换位置。用图的内容命名。

-

In case of you have many files, say $\ge$ 10 files, and your file names include numbers to indicate order, make sure to pad them with the appropriate number of zeros, so that (e.g.) 11 doesn’t get sorted before 2.

# good file names 01-load-data.R 02-exploratory-analysis.R 03-model-approach-1.R 04-model-approach-2.R # chronological order 2025-01-01-report.Rmd 2025-02-01.report.RmdDon’t use “final” or similar words in file names. Put the date in the file name to indicate historical versions.

# good report-2022-03-20.qmd report-2022-04-02.qmd # bad finalreport.qmd FinalReport-2.qmd

-

-

Write project file structure guide, i.e., a ReadMe file, as the project progresses;

-

When working on big projects, it’s worth keeping notes on key variables to help keep track of everything;

-

Avoid repetition; organize code frequently;

- If something is no longer used but you want to keep it as a historical record, label it as “deprecated.”

Internal Structure

具体每个 script

-

Order of code

- Call your libraries on top of code

- Set all default variables or global options and all the path variables at the top of the code.

- Source all the code at the beginning

- Call all the data-files at the top

-

Put all the external dependencies on top of your code in the following order:

- Libraries are external to the file.

- path variables

- other files apart from one you are working is external as well.

- databases and CSV

# load libraries ------------------------------------------- # set defaults --------------------------------------------- # source files --------------------------------------------- # get Data ------------------------------------------------- -

Name variables meaningfully and consistently.

For variables that hold the same type of data, use a consistent naming scheme:

- Start with the same context or base name

- Use suffixes to indicate variations

E.g.,

gfrstands for general fertility rategfr_sq:gfr^2, squared termcgfrordgfr: change ingfr:gfr–gfr_1.gfr_1: first order laggedgfrgfr_2: second order laggedgfr

See more about naming conventions HERE

-

File path

Avoid using absolute path. Store file names in variables so you can change easily. -

If your script uses add-on packages, load them all at once at the very beginning of the file.

Do NOT uselibrary()calls throughout your code or having hidden dependencies that are loaded in a startup file, such as.Rprofile. ❌ -

Prefer

TRUEandFALSEoverTandF. -

If you use larger numbers, use scientific annotations

1e6for million as zeros are hard to count when there are many but1e6indicates 6 zeros directly.

Indentation

-

Spaces over Tabs

It is recommended to use spaces over Tabs for consistency across different systems and editors.

For example, a Tab is 4 spaces on Windows and 8 spaces on Linux.

-

One indentation can be 2 or 4 spaces.

- 4 spaces are used in Python

- 2 spaces are used in CSS, js, that need many nested levels with long lines.

-

Vertical alignment

Continuation lines should align wrapped elements vertically.

function arguments align with opening delimiter 函数参数与起始括号对齐

# Good # Aligned with opening delimiter. foo = long_function_name(var_one, var_two, var_three, var_four) # Another example foo2 <- function( first_arg, second_arg, third_arg ){ create_file <- readxl::read_excel(path = first_arg, sheet = second_arg, range = third_arg) } -

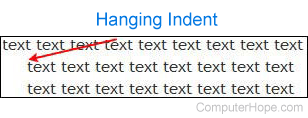

Hanging indent

Q: What is a hanging indent?

A: Alternatively called a negative indent, a hanging indent is an indent that indents all text except the first line. Below is an example of a hanging indent, which is commonly used in a bibliography.

Could use a hanging indent where there should be no arguments on the first line (i.e., the last non-whitespace character of the line is the opening parenthesis) and further indentation should be used to clearly distinguish itself as a continuation line until the closing parenthesis.

# Good Examples # Add 4 spaces (an extra level of indentation) to distinguish arguments from the rest. def long_function_name( var_one, var_two, var_three, var_four): print(var_one) long_function_name <- function( a = "a long argument", b = "another argument", c = "another long argument" ) { # As usual code is indented by two spaces. } # Hanging indents *may* be indented to other than 4 spaces. # Indent by 2 spaces foo = long_function_name( var_one, var_two, var_three, var_four) # Indent by 4 spaces foo = long_function_name( var_one, var_two, var_three, var_four) # Add 4 spaces (an extra level of indentation) to # distinguish arguments from the rest. def long_function_name( var_one, var_two, var_three, var_four): print(var_one) # Bad # Arguments on first line forbidden when not using vertical alignment. # This makes it hard to spot where the definition begins and ends. foo = long_function_name(var_one, var_two, var_three, var_four) # Hanging indents should add a level. # Further indentation required as indentation is not distinguishable. def long_function_name( var_one, var_two, var_three, var_four): print(var_one) # Good # Add some extra indentation on the conditional continuation line. # This creates distinguishment. if (this_is_one_thing and that_is_another_thing): do_something() -

The closing delimiter (e.g., brace/bracket/parenthesis) on multiline constructs may

- either line up under the first non-whitespace character of the last line of list, as in:

# line up under the first non-whitespace character my_list = [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, ] result = some_function_that_takes_arguments( 'a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', )- or it may be lined up under the first character of the line that starts the multiline construct, as in:

# line up with the variable definition my_list = [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, ] result = some_function_that_takes_arguments( 'a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', )

Line Break for Binary Operators

Operator goes to the next line.

# line break "before" binary operators

income = (gross_wages

+ taxable_interest

+ (dividends - qualified_dividends)

- ira_deduction

- student_loan_interest)

Spacing

- Place spaces around all infix operators (

=,+,-,<-, etc. 中缀运算符). - The same rule applies when using

=(as assignment operator) in function calls. -

Always put a space after a comma, and never before.

# Good x[,␣1] average <- mean(feet / 12 + inches, na.rm = TRUE) # Bad x[,1] x[␣,1] # space before comma x[␣,␣1] # space before and after comma average<-mean(feet/12+inches,na.rm=TRUE)

There are a few exceptions, where infix operators should NEVER be surrounded by spaces:

-

The operators with high precedence:

::,:::,$,@,[,[[,^, unary-, unary+, and:.# Good sqrt(x^2 + y^2) df$z x <- 1:10 # Bad sqrt(x ^ 2 + y ^ 2) df $ z x <- 1 : 10 -

Single-sided formulas when the right-hand side is a single identifier.

# Good ~foo tribble( ~col1, ~col2, "a", "b" ) # Bad ~ foo tribble( ~ col1, ~ col2, "a", "b" ) -

Note that single-sided formulas with a complex right-hand side do need a space.

# Good ~ .x + .y # Bad ~.x + .y -

When used in tidy evaluation

!!(bang-bang) and!!!(bang-bang-bang) (because they have precedence equivalent to unary-/+).# Good call(!!xyz) # Bad call(!! xyz) call( !! xyz) call(! !xyz)

Code Sessions

Another important use of comments is to break up your file into easily readable chunks. Use long lines of - and = to make it easy to spot the breaks.

# Load data --------------------------------------

# Plot data ======================================

The long lines are more visible, but you can create sections by adding 4 dashes (-), 4 equals (=), or 4 hash symbols (#).

# some comment ----

# some comment ====

# some comment ####

You can also create subsection in R by adding hash symbols in front of a section.

## some comment ----

### some comment ----

#### some comment ----

Pipes

- Migrate from

magrittr’s%>%to the native pipe|>. - Same keyboard shortcut: ⇧⌘M

Parentheses

Do NOT place spaces around code in parentheses or square brackets.

# Good

if (debug) do(x)

diamonds[5,␣]

# Bad

if ( debug ) do(x) # No spaces around debug

x[1,] # Needs a space after the comma

x[1␣,] # Space goes after comma not before

Do NOT put spaces inside or outside parentheses for regular function calls.

# Good

mean(x, na.rm = TRUE)

# Bad

mean␣(x, na.rm = TRUE)

mean(␣x, na.rm = TRUE␣)

Place a space before and after () when used with if, for, or while.

# Good

if␣(debug)␣{

show(x)

}

# Bad

if(debug){

show(x)

}

Place a space after () used for function arguments:

# Good

function(x)␣{}

# Bad

function (x) {}

function(x){}

Embracing Operator {{

The embracing operator, “{{” (curly-curly operator), should always have inner spaces to help emphasis its special behavior:

# Good

max_by <- function(data, var, by) {

data |>

group_by({{␣by␣}}) |>

summarise(maximum = max({{ var }}, na.rm = TRUE))

}

# Bad

max_by <- function(data, var, by) {

data |>

group_by({{by}}) |>

summarise(maximum = max({{var}}, na.rm = TRUE))

}

Braced Expressions {

Distinguish the embracing operator from braced expressions, {}

It allows you to group multiple R expressions together into a single expression. The most common places to use braced expressions are in function definitions, control flow, and in certain function calls (e.g. tryCatch() and test_that()).

To make this hierarchy easy to see:

-

{An opening curly brace should be the last character on the line.

Related code (e.g., anifclause, a function declaration, a trailing comma, …) must be on the same line as the opening brace.{should never go on its own line and should always be followed by a new line. -

}A closing curly brace should be the first character on the line.}should always go on its own line, unless it’s followed byelse.

# Good

if (y < 0 && debug) {

message("y is negative")

}

if (y == 0) {

if (x > 0) {

log(x)

} else {

message("x is negative or zero")

}

} else {

y^x

}

test_that("call1 returns an ordered factor", {

expect_s3_class(call1(x, y), c("factor", "ordered"))

})

# It’s ok to leave very short statements on the same line

if (y < 0 && debug) message("Y is negative")

Functions

Naming

-

Function names should tell what the function does. It should be short, but it’s better to be clear than short, as coding editors’ autocomplete makes it easy to type long names.

Use informative names, e.g., sales_data_2020, api_token, rate_of_interest.

-

Generally function names should be verbs, and argument/variable name should be nouns.

-

Don’t include dots ( . ) in names.

Base R uses dots in function names (

contrib.url()) and class names (data.frame), but it’s better to reserve dots exclusively for the S3 object system.In S3, methods are given the name

function.class; if you also use.in function and class names, you end up with confusing methods likeas.data.frame.data.frame(). - Nouns are ok if the function computes a very well known noun.

mean()is better thancompute_mean()andcoef()is better thanget_coefficients()- A good sign that a noun might be a better choice is if you’re using a very broad verb like “get”, “compute”, “calculate”, or “determine”. ❌

# Too short f() # Not a verb, or descriptive my_awesome_function() # Long, but clear impute_missing() collapse_years() -

Use a short unique prefix to group related names together.

For instance, functions in

stringrpkg start withstr_, e.g.,str_sub,str_split. -

You may prefix data-types before variable names.

int_currency <- 1:10 chr_letters <- letters dt_mtcars <- data.table::data.table(mtcars) tbl_mtcars <- tibble::tibble(mtcars) # `num_` indicates numerical values so you don't put strings join <- function(num_x, num_y) num_x + num_y -

snake_case, where each lowercase word is separated by an underscore.CamelCaseorcamelCase(differs fromCamelCaseby initial lowercase character) is a popular alternative.- Other options:

UPPERCASE,UPPER_CASE_WITH_UNDERSCORES - Note: When using acronyms in

CamelCase, capitalize all the letters of the acronym. Thus HTTPServerError is better than HttpServerError. - Do NOT use

Capitalized_Words_With_Underscores. - It doesn’t really matter which one you pick, the important thing is to be consistent: pick one or the other and stick with it.

# Never do this! col_mins <- function(x, y) {} rowMaxes <- function(y, x) {}- If you have a family of functions that do similar things, make sure they have consistent names and arguments.

Use a common prefix to indicate that they are connected. That’s better than a common suffix because autocomplete allows you to type the prefix and see all the members of the family.

# Good input_select() input_checkbox() input_text() # Not so good select_input() checkbox_input() text_input() - The arguments to a function typically fall into two broad sets:

-

Data arguments supply the data to compute on, and

-

Detail arguments supply arguments that control the details of the computation.

-

Generally, data arguments should come first. Detail arguments should go on the end, and usually should have default values.

-

Arbitrary number of inputs. When you see

…(dot-dot-dot), it captures any number of arguments that aren’t otherwise matched.In other programming languages, this type of argument is often called varargs (short for variable arguments), and a function that uses it is said to be variadic.

Usa example of

...i01 <- function(y, z) { list(y = y, z = z) } i02 <- function(x, ...) { i01(...) } str(i02(x = 1, y = 2, z = 3)) #> List of 2 #> $ y: num 2 #> $ z: num 3 # ---------------------------------- # Use `..N` to refer to elements of `...` by position. i03 <- function(...) { list(first = ..1, third = ..3) } str(i03(1, 2, 3)) #> List of 2 #> $ first: num 1 #> $ third: num 3If your function takes a function as an argument, you want some way to pass additional arguments to that function. In this example,

lapply()uses...to passna.rmon tomean():x <- list(c(1, 3, NA), c(4, NA, 6)) str(lapply(x, mean, na.rm = TRUE)) #> List of 2 #> $ : num 2 #> $ : num 5

-

-

Always use named parameters

Named parameters are more readable.

# Code with named parameters call_cognitive_endpoint( endpoint = speech$get_endpoint(), operation = "models/base", body = list(), options = list(), headers = list(`content-type` = 'audio/wav'), http_verb = "POST" ) # ----------------- # Code without named parameters call_cognitive_endpoint( speech$get_endpoint(), "models/base", list(), list(), list(`content-type` = 'audio/wav'), "POST" )

In mean(x, trim = 0, na.rm = FALSE), the data is x, and the details are how much data to trim from the ends (trim) and how to handle missing values (na.rm).

- The default value of detailed argument should almost always be the most common value. The few exceptions to this rule are to do with safety. For example, it makes sense for

na.rmto default toFALSEbecause missing values are important. Even thoughna.rm = TRUEis what you usually put in your code, it’s a bad idea to silently ignore missing values by default. - When you call a function, you typically

- omit the names of the data arguments, because they are used so commonly.

- If you override the default value of a detail argument, you should use the full name.

# Good mean(1:10, na.rm = TRUE) # Bad mean(x = 1:10, , FALSE) mean(, TRUE, x = c(1:10, NA)) - You can refer to an argument by its unique prefix (e.g.

mean(x, n = TRUE)), but this is generally best avoided given the possibilities for confusion.

Documenting Functions

Comments

- Capitalize first letter

- If 1 sentence, don’t add period; if >1 sentence, add period.

- Add a single space after

# - Paragraphs inside a block comment are separated by a line containing a single

#.

Insert Roxygen Comments: ⇧⌥⌘R

- Useful for R package documentation

- Similar to Python’s docstring

- Q: Can regular functions (not in a package) be documented using the same syntax?

The inserted code looks like this:

#' @title Make shades (Title of the function)

#'

#' @description

#' Given a colour make n lighter or darker shades (Detailed description of the function)

#'

#' @param colour The colour to make shades of

#' @param n The number of shades to make

#' @param lighter Whether to make lighter (TRUE) or darker (FALSE) shades

#'

#' @return A vector of n colour hex codes

#' @export

#'

#' @examples Provide some examples of how to use your function

#' # Five lighter shades

#' make_shades("goldenrod", 5)

#' # Five darker shades

#' make_shades("goldenrod", 5, lighter = FALSE)

make_shades <- function(colour, n, lighter = TRUE) {

[your function code here ...]

}

Roxygen comments all start with #'.

- Put at the top of your function.

@title: The first line is the title of the function then there is a blank line.@description: Following that there can be a paragraph giving a more detailed description of the function.- The keywords

@titleand@descriptioncan be left off (not the text, just the@…part), but title text should be in line 1, then a blank line (#’only), and then the description text. - The next section describes the parameters (or arguments) for the function marked by the

@paramfield.

Provide the type and a short description of function inputs. - The next field is

@return. This is where we describe what the function returns.

Provide the type and a short description of function outputs. @exportadds your function to your NAMESPACE. Adding@exporttells Roxygen that this is a function that we want to be available to the user.@examplesis where we put some short examples showing how the function can be used.

Which custom functions are called from this function (or from where was this function called - imagine a directed graph).

Another example of a function documented with Roxygen

#' Plot colours

#'

#' Plot a vector of colours to see what they look like

#'

#' @param colours Vector of colour to plot

#'

#' @return A ggplot2 object

#' @export

#'

#' @importFrom rlang .data

#'

#' @examples

#' shades <- make_shades("goldenrod", 5)

#' plot_colours(shades)

plot_colours <- function(colours) {

plot_data <- data.frame(Colour = colours)

ggplot2::ggplot(plot_data,

ggplot2::aes(x = .data$Colour, y = 1,

fill = .data$Colour,

label = .data$Colour)) +

ggplot2::geom_tile() +

ggplot2::geom_text(angle = "90") +

ggplot2::scale_fill_identity() +

ggplot2::theme_void()

}

Data Management

-

Always keep a copy of the original data.

-

Don’t use numbers for columns

Index with names in stead of numbers whenever possible.

# Good > mtcars[1, c("mpg","disp","hp","drat", "vs")] # Bad > mtcars[1, c(1,3:5, 8)]

References:

R for Data Scince, https://r4ds.had.co.nz/functions.html

R package development workshop, https://combine-australia.github.io/r-pkg-dev/other-documentation.html

Tidyverse Style Guide, https://style.tidyverse.org

Google’s R Style Guide, https://web.stanford.edu/class/cs109l/unrestricted/resources/google-style.html

Python Style Guide, https://peps.python.org/pep-0008/

Best Coding Practices for R, https://bookdown.org/content/d1e53ac9-28ce-472f-bc2c-f499f18264a3/